Hybridizaiton Between JUNIPERUS BERMUDIANA AND J. VIRGINIANA IN BERMUDA

by Robert P Adams & David Wingate

Hybridization in Bermuda’s Cedars: What the Research Reveals

The document titled HYBRIDIZATION BETWEEN Juniperus bermudiana AND J. virginiana IN BERMUDA offers an in‑depth scientific examination of one of the most important ecological stories in Bermuda: the struggle of the native Bermuda cedar to survive, the introduction of mainland juniper species, and the genetic mixing now occurring between them. Authored by Robert P. Adams and David Wingate, the study combines historical context, DNA analysis, and field observations to understand how hybridization is reshaping Bermuda’s iconic conifer.

This research provides essential insight for conservationists, land managers, and anyone interested in the island’s natural heritage.

A Crisis That Changed Bermuda’s Forests

In the mid‑20th century, Bermuda experienced a devastating ecological event. Two scale insects, accidentally introduced around 1942, attacked the native Bermuda cedar (Juniperus bermudiana). By 1955, an estimated 90% of the trees had died, and by the late 1970s, the figure had climbed to nearly 99%.

With the island’s dominant tree species collapsing, residents and horticulturalists sought alternatives.

Two Replacement Cedars Enter the Landscape

Two non‑native junipers were introduced as substitutes:

Darrell’s cedar — brought from a Florida nursery in the 1940s

Smith’s cedar — brought into Bermuda in the 1950s, believed at the time to be Juniperus barbadensis

These trees were planted widely because they resisted the scale insects that destroyed the Bermuda cedar. As the study confirms, this resistance comes from their mainland origins, where such insects already occur.

However, introducing these species set the stage for genetic mixing with the native cedar.

What the DNA Analyses Show

The study uses detailed molecular tools, including nuclear DNA (nrDNA) and chloroplast DNA (trnC–trnD), to determine the identity of these introduced cedars and evaluate hybridization.

Key findings include:

Darrell’s cedar is actually Juniperus virginiana var. silicicola

Smith’s cedar is Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana

Both species are closely related to J. bermudiana and can readily cross with it

F1 hybrids were identified, showing mixed genetic signatures

Some individuals showed evidence of complex backcrossing involving all three taxa

These discoveries confirm that hybridization is already occurring in Bermuda’s modern cedar population.

Why Hybridization Matters

Hybridization between native and introduced junipers raises two major concerns:

1. Loss of Native Genetic Integrity

If hybrid trees produce fertile offspring, genes from mainland junipers will gradually replace pure J. bermudiana genetics. Over time, the unique characteristics of the Bermuda cedar—shaped by centuries of isolation—could be diluted or lost entirely.

2. Landscape Dominance by Introduced Types

Darrell’s and Smith’s cedars grow vigorously and resist pests. Consequently, they are often chosen when replacing dead or diseased native trees. As they populate roadsides, parks, and private gardens, the opportunities for cross‑pollination increase dramatically.

This creates a cycle:

Fewer pure Bermuda cedars

More hybrids

More non‑native genes in future generations

The study warns that this trend, if unmanaged, may ultimately erase the island’s native cedar lineage.

Visible Differences and Field Observations

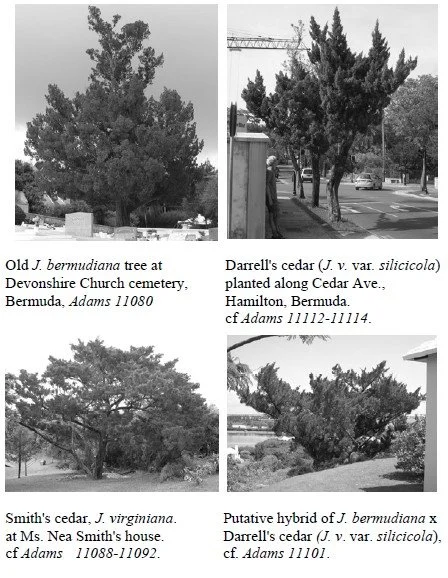

The document provides field photographs and notes on the morphological differences between tree types. For example:

Darrell’s cedar has finer foliage, a more compact habit, and leaves arranged in threes.

Hybrids often show intermediate characteristics, making them visually distinct from both parent species.

Some trees appear almost pure but carry subtle genetic markers of hybridization, suggesting backcrossing over generations.

These visual cues, paired with DNA evidence, give land managers practical tools for identifying hybrid individuals in the field.

Implications for Conservation and Landscaping

This study highlights the need for:

Active protection and propagation of pure Bermuda cedars

Careful selection of planting materials to avoid unintentional hybridization

Public awareness about the differences between native and introduced cedars

Long‑term monitoring to track the genetic status of wild and cultivated populations

The research makes clear that while imported junipers helped restore greenery after the Cedar Blight, their widespread planting now threatens the survival of Bermuda’s true endemic cedar.

A Call to Preserve Bermuda’s Botanical Identity

The Bermuda cedar is more than just a tree—it is a cultural and ecological symbol woven deeply into the island’s history. This document serves as both a scientific analysis and an urgent reminder. Hybridization is not a future possibility; it is happening now. The choices made by homeowners, landscapers, and environmental stewards will determine whether pure Juniperus bermudiana continues to exist as a distinct species in its only native home.

If you want, I can refine this post for your website’s style, create a shorter public‑friendly version, or build accompanying educational content about Bermuda’s cedar species.