Notes on the Flora of The Bermudas

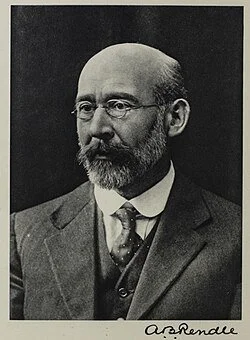

by A B Rendle F.R.S. 1937

Understanding Bermuda’s Botanical Heritage: A Look Inside Notes on the Flora of the Bermudas (Rendle, 1937)

The 1937 re‑publication of Dr. A. B. Rendle’s Notes on the Flora of the Bermudas remains one of the most valuable botanical records ever produced for the islands. Originally written after Rendle’s ten‑week visit in 1933 and published in the Journal of Botany in 1936, this document offers a rare and detailed snapshot of Bermuda’s plant life during a pivotal time in its ecological history.

For anyone interested in Bermuda’s natural environment—gardeners, conservationists, botanists, educators, or visitors—this resource serves as an essential window into the islands’ native flora, endangered species, naturalized plants, and changing landscapes.

A Flora in Constant Transition

Rendle begins by acknowledging a truth that still holds today: Bermuda’s flora is continually reshaped by human activity. As land was cleared for farming, homes, roads, and golf courses, the original vegetation dwindled. At the same time, people introduced plants from across the world—some decorative, some agricultural—and many took permanent hold in Bermuda’s mild climate.

Because of this ongoing transformation, Rendle stressed the importance of periodically taking stock of which species remain abundant, which are declining, and which newcomers are altering the local ecosystems. His 1933 work represents one such crucial moment of observation.

Native and Endemic Plants: Bermuda’s Botanical Identity

One of the strongest contributions of Rendle’s survey is its detailed attention to truly native and endemic species—those that evolved on the islands or arrived naturally long before modern settlement.

He highlights three iconic endemic trees:

Juniperus bermudiana (Bermuda Cedar) — once covering much of the island, heavily logged for shipbuilding, yet still a defining feature in the 1930s.

Sabal bermudana (Bermuda Palmetto) — widespread and historically vital, threatened by scale insects that were already a concern during Rendle’s visit.

Elacodendron Laneanum — a rare evergreen limited to rocky slopes near Harrington Sound and Castle Harbour, already on the brink of extinction.

Rendle also details several smaller endemic plants, including the national flower, Sisyrinchium bermudiana, and Erigeron Darrellianus, a daisy-like species common on rocky coasts.

These species form the core of Bermuda’s botanical identity and remain central to conservation efforts today.

Paget Marsh and Bermuda’s Wetlands

A major focus of the document is Bermuda’s marshland ecosystems, especially Paget Marsh, which Rendle believed should be “preserved at all costs.” In the 1930s, it represented one of the last areas still reflecting the islands’ original lowland vegetation.

Rendle describes a thriving habitat filled with:

Dense stands of Bermuda Palmetto

Rare sedges such as Carex bermudiana

Ferns including Osmunda regalis, O. cinnamomea, and Adiantum bellum

Shade-loving vines, shrubs, and mosses

Naturalized fruit trees and scattered introduced ornamentals

This marsh, along with others like Devonshire, Pembroke, and Warwick, offered insights into how Bermuda’s wetlands once functioned before drainage, reclamation, and development changed them.

Coastal Plant Life: Survivors on the Edge

Bermuda’s coastlines host a distinctive group of salt‑tolerant and wind‑shaped plants. Rendle documents species that anchored dunes, clung to cliffs, and adapted to extreme coastal conditions, such as:

Ipomoea pes‑caprae and Canavalia lineata, important sand stabilizers

Scaevola plumieri and Heliotropium gnaphalodes, flourishing behind beaches

Coccoloba uvifera (Sea Grape), particularly striking along the South Shore

Opuntia dillenii, Bermuda’s native prickly pear cactus, forming rugged coastal clumps

These plants illustrate Bermuda’s natural resilience and are still recognized today for their ecological importance along the shoreline.

The Growing Influence of Introduced Species

Rendle’s observations show that by the 1930s, introduced species were already outnumbering native ones. He recorded approximately 300 naturalized plant species, compared with about 146 native flowering species.

Prominent introduced plants included:

Oleander, wild almost everywhere and widely used for hedges

Lantana species, aggressively dominating hillsides

Eugenia uniflora (Surinam Cherry)

Pimenta officinalis (Allspice)

Wild Sisal (Furcraea macrophylla), forming massive, smothering clumps

Many of these remain commonplace in Bermuda today, hinting at how deeply human activity has shaped the islands’ plant communities.

Historical Context and Early Botanical Records

The document also provides fascinating historical context. Rendle references earlier botanists such as Dr. N. L. Britton, John Dickinson, and even Captain John Smith, who described Bermuda’s vegetation following the 1609 wreck of the Sea Venture. Their records—some only fragments—help piece together how dramatically Bermuda’s flora has changed over centuries.

Why This Document Matters Today

Rendle’s work is more than a botanical catalogue. It is:

A record of species now rare, threatened, or extinct

A snapshot of habitats before modern development

A guide for conservation priorities

A bridge between early botanical history and modern science

For your work with the Botanist Café and educational content, this resource provides narrative depth, historical authority, and a foundation for storytelling about Bermuda’s botanical world.

If you’d like, I can now create:

A shorter version tailored specifically for the Botanist Café website

A multi‑part educational series

Interpretive content for displays, signs, or publications